No doubt you're aware that it's easier and more cost-effective to

sell to existing clients than to new ones. That's reflected in the fact

that 70% of architectural and engineering firms' work comes from repeat

clients. So naturally most firms make it a priority to sell additional

services—what's called cross selling—to existing clients.

Unfortunately, this common-sense approach falls short more often than

not. Lack of success with cross selling is among the most common

complaints I hear when helping firms improve their rainmaking process.

Why is this so difficult? Here are the reasons I uncover most often, and

what you can do to overcome them:

Discomfort selling outside your area of expertise.

Not that this is a legitimate reason why cross selling doesn't work, but

it certainly qualifies as a popular excuse. Ironically, many of these

same professionals who feel inadequate to cross disciplinary boundaries

to talk to clients about their needs will gladly pass the torch to the

firm's business development specialist— despite that individual's lack of technical credentials.

Solution: Specific expertise can be a hindrance rather than a help

in sales. It tempts you to look for problems that fit your skills

rather than openly exploring needs from the client's perspective. Learn

to ask great questions and develop your general problem solving abilities. Then bring in the proper expertise when necessary.

Management inadvertently promotes a lack of cooperation between business units. The

fact is that many firm leaders complain about the paucity of cross

selling while ratcheting up the pressure for individual business units

to meet their sales budgets. You can't expect people to look out for the

greater corporate good when the focus (and the pressure) is

predominantly on how well their own group performs.

Solution: Reward people for succeeding at cross selling, or

dispense with the notion that it will ever work. The firms that excel at

cross selling are typically those that actively promote cross-business unit collaboration in general. Or better still, they organize as a single profit center to minimize the inter-company competition.

The difficulty of engaging different buyers within your clients' organizations.

In concept, it seems straightforward to expand business with your best

clients. But the reality is often quite different. For much the same

reason as my previous point, your current client contacts may not be

that motivated to introduce your firm to other parts of their organization.

They may love you, but what's in it for them? Plus they may not know

their colleagues in other business units well enough to provide you much

leverage.

Solution: Selling succeeds when you can create win-win

scenarios. The same is true in motivating your clients to help you cross

sell. Focus on those opportunities where it's in their interest

for you to serve other parts of their organization. For example, can

you export a winning solution or approach to another business unit where

your client contact gets the credit?

Distrust in your colleagues to deliver. Most

professionals are understandably reluctant to entrust their client

relationships to peers who might not uphold the same standard of care.

So they resist cross selling efforts involving individuals or groups

they aren't confident will come through. This situation is far more

common than many firms recognize because it's rarely discussed openly.

Solution: If you suspect this problem exists in your firm,

it's best to investigate it through private conversations. To encourage

transparency, avoid taking sides or putting people on the

defensive—simply uncover the facts (remember, perceptions in such

matters effectively form the reality of the situation). Once you feel

you understand the concerns, then work with the involved parties to try

to resolve the issues identified.

Lack of client focus. I once participated in a

planning meeting where one of the firm's executives began sketching a

matrix that listed their top clients and what services they were

providing to each. The purpose of this exercise was to identify where

their best cross selling opportunities existed. But the most important

question was ignored: What other needs do our clients have that we might

help them with?

Perhaps the most prominent reason cross selling doesn't work is the

lack of true client focus. When you approach the issue motivated by self

interest, you're unlikely to have many productive conversations with

clients about new services. Don't you think they can detect what's

really driving your interest in the subject?

If you're genuinely motivated to serve your clients, cross selling

becomes a natural byproduct of your commitment to help. It's driven by

the client's needs, not your firm's desire to sell more. Plus, client

focus is the secret to overcoming most of the problems listed above.

There should be no discomfort in serving, no lack of incentive to help

clients succeed. Navigating the client's organization is easier when you

offer true business value. And subpar service and quality within your

firm is no longer tolerated.

So my advice for cracking the code on cross selling is this: Pursue a

culture of true client focus. It's not a quick fix, but it is the most

powerful way to solve your shortcomings at cross selling—not to mention a

whole host of other corporate benefits.

No doubt you're aware that it's easier and more cost-effective to

sell to existing clients than to new ones. That's reflected in the fact

that 70% of architectural and engineering firms' work comes from repeat

clients. So naturally most firms make it a priority to sell additional

services—what's called cross selling—to existing clients.

Unfortunately, this common-sense approach falls short more often than

not. Lack of success with cross selling is among the most common

complaints I hear when helping firms improve their rainmaking process.

Why is this so difficult? Here are the reasons I uncover most often, and

what you can do to overcome them:

Discomfort selling outside your area of expertise.

Not that this is a legitimate reason why cross selling doesn't work, but

it certainly qualifies as a popular excuse. Ironically, many of these

same professionals who feel inadequate to cross disciplinary boundaries

to talk to clients about their needs will gladly pass the torch to the

firm's business development specialist— despite that individual's lack of technical credentials.

Solution: Specific expertise can be a hindrance rather than a help

in sales. It tempts you to look for problems that fit your skills

rather than openly exploring needs from the client's perspective. Learn

to ask great questions and develop your general problem solving abilities. Then bring in the proper expertise when necessary.

Management inadvertently promotes a lack of cooperation between business units. The

fact is that many firm leaders complain about the paucity of cross

selling while ratcheting up the pressure for individual business units

to meet their sales budgets. You can't expect people to look out for the

greater corporate good when the focus (and the pressure) is

predominantly on how well their own group performs.

Solution: Reward people for succeeding at cross selling, or

dispense with the notion that it will ever work. The firms that excel at

cross selling are typically those that actively promote cross-business unit collaboration in general. Or better still, they organize as a single profit center to minimize the inter-company competition.

The difficulty of engaging different buyers within your clients' organizations.

In concept, it seems straightforward to expand business with your best

clients. But the reality is often quite different. For much the same

reason as my previous point, your current client contacts may not be

that motivated to introduce your firm to other parts of their organization.

They may love you, but what's in it for them? Plus they may not know

their colleagues in other business units well enough to provide you much

leverage.

Solution: Selling succeeds when you can create win-win

scenarios. The same is true in motivating your clients to help you cross

sell. Focus on those opportunities where it's in their interest

for you to serve other parts of their organization. For example, can

you export a winning solution or approach to another business unit where

your client contact gets the credit?

Distrust in your colleagues to deliver. Most

professionals are understandably reluctant to entrust their client

relationships to peers who might not uphold the same standard of care.

So they resist cross selling efforts involving individuals or groups

they aren't confident will come through. This situation is far more

common than many firms recognize because it's rarely discussed openly.

Solution: If you suspect this problem exists in your firm,

it's best to investigate it through private conversations. To encourage

transparency, avoid taking sides or putting people on the

defensive—simply uncover the facts (remember, perceptions in such

matters effectively form the reality of the situation). Once you feel

you understand the concerns, then work with the involved parties to try

to resolve the issues identified.

Lack of client focus. I once participated in a

planning meeting where one of the firm's executives began sketching a

matrix that listed their top clients and what services they were

providing to each. The purpose of this exercise was to identify where

their best cross selling opportunities existed. But the most important

question was ignored: What other needs do our clients have that we might

help them with?

Perhaps the most prominent reason cross selling doesn't work is the

lack of true client focus. When you approach the issue motivated by self

interest, you're unlikely to have many productive conversations with

clients about new services. Don't you think they can detect what's

really driving your interest in the subject?

If you're genuinely motivated to serve your clients, cross selling

becomes a natural byproduct of your commitment to help. It's driven by

the client's needs, not your firm's desire to sell more. Plus, client

focus is the secret to overcoming most of the problems listed above.

There should be no discomfort in serving, no lack of incentive to help

clients succeed. Navigating the client's organization is easier when you

offer true business value. And subpar service and quality within your

firm is no longer tolerated.

So my advice for cracking the code on cross selling is this: Pursue a

culture of true client focus. It's not a quick fix, but it is the most

powerful way to solve your shortcomings at cross selling—not to mention a

whole host of other corporate benefits.

If you're not a strong writer, the last thing you want to do is take a stream-of-consciousness approach to writing. Yet that's what I routinely observe among the technical professionals I work with. The result is often akin to this excerpt from an engineering firm's project management handbook:

If you're not a strong writer, the last thing you want to do is take a stream-of-consciousness approach to writing. Yet that's what I routinely observe among the technical professionals I work with. The result is often akin to this excerpt from an engineering firm's project management handbook:

Some documents are constrained to repetitiveness by factors such as regulatory requirements, work type, site information, and intent. In such cases, it is permissible to develop standard language to maximize consistency and efficiency. In such instances, a special review of the standard language must be performed to verify that applicable regulations and requirements have been considered.

Huh? I'm sure if I asked the author what he meant, he could explain it clearly to me. But by putting little forethought into his writing he ended up with something that was incomprehensible. It's one thing to do this in an internal document, but I commonly see this kind of writing in proposals, reports, letters, emails, and other communications with clients and other outside parties. That's hardly a good reputation builder!

The poor writing I see is largely the outcome of a thinking problem—or more precisely, an unthinking problem. In an industry populated by really smart people, there's no excuse for writing without first thinking about what you're trying to say. Perhaps it would help to have a process for planning your writing. Here are some suggested steps:

Think in terms of bullet points. When you jump right into writing without a plan, there's a tendency to get too caught up in how you're saying it before you've really determined what to say. Have you ever spent an inordinate amount of time writing your first few paragraphs? I have—when I didn't plan first. At the start, don't think about sentences—and certainly not paragraphs—think in terms of bullet points. Build your detailed content outline (as described below) by listing short phrases like "slow air flow a concern" or "compressed schedule is key" before you write any sentences.

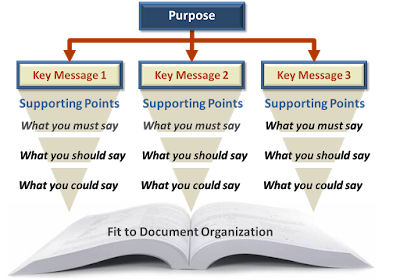

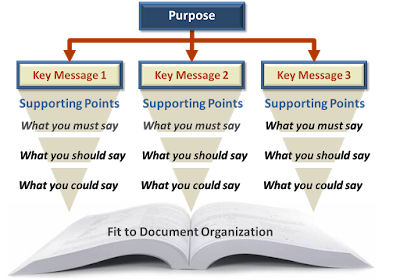

First define your purpose. Power Writing is writing to achieve a specific desired result. That obviously means you must first define what it is you want to accomplish. Sounds simple enough, but identifying the purpose of writing assignments is surprisingly uncommon in A/E firms. It's important to be specific. For example: "The purpose of this report is to show that the extent of contamination at the site is considerably less than previously determined."

Then determine your key messages. These are 3-5 points that need to be effectively communicated to accomplish your purpose. One exercise I recommend to help you distill your key messages is called the "two-minute drill." Imagine you had to verbally present the essence of your entire document in only two minutes. What would you say? What are the main points that you absolutely would need to make? These are the key messages that should drive the content of your document.

For each key message, list your supporting points. If one of your key messages, for example, is "save money on O&M through different design options," then what do you need to say to convincingly make your case? Your supporting points generally serve three primary functions: (1) describe (give clarity), (2) validate (give proof), and (3) illustrate (give examples). Technical professionals often over-describe, under-validate, and completely ignore providing illustrations. At this stage, though, don't worry about the quantity or balance of your supporting points; list everything you can think of.

Organize your supporting points in descending order of importance. This applies the old journalistic standard of the "inverted pyramid." Why? Because most people don't read your documents word for word; they skim. So you want your most important information up front—in your document, chapters, paragraphs. Organizing your supporting points at this stage facilitates your use of the inverted pyramid when you're writing.

Another benefit of organizing your supporting points is helping you pare down your content to no more than is needed. My suggestion is to place each supporting point under one of three headings: (1) what I must say, (2) what I should say, and (3) what I could say. Many (if not most) of the points falling in that last category are candidates for the cutting room floor.

Fit your content outline to the document structure. To this point you've based your outline on importance rather than the flow of the document. Now you need to translate it into whatever document structure is necessary. This can be difficult, but without the planning steps above you'd be much more likely to omit or obscure your key messages. Beware of slavish devotion to a traditional document outline. You may determine that a reorganization is appropriate to feature your most important content. For example, I favor putting conclusions and recommendations—your most important information—at the front of a report rather than the traditional position in the back.

Now you can start writing. Having built a detailed content outline and fitted it to your document structure, the writing comes much easier—and the result will be much better. By the way, this process is even more powerful for team writing assignments. Rather than the usual divide-and-conquer approach, get your team together to work through the above planning process. The collective brainstorming is much more likely to lead to a document that will get the results you want.

Many (if not most) technical professionals are ineffective writers. That fact is widely

acknowledged. The question is does anyone really care? I don't see A/E

firms investing much in helping their staff become more proficient

writers.

Perhaps

they haven't considered the costs of poor writing: Lost proposals, weak

marketing, unapproved solutions, project mistakes, client claims,

interoffice conflict, lost productivity—to name a few. I have seen all

of these over the years as a result of poorly written proposals,

reports, contracts, policies, correspondence, emails, or procedures.

On

the flip side, strong writing can yield substantial business benefits.

I'm hardly a distinguished writer, but I've compiled a 75% proposal win

rate over the last 20 years, producing more than $300 million in fees. I

helped my previous employer generate millions of dollars in new

business that started with prospective clients contacting us because of

something we'd written. I wrote letters to regulatory agencies making

the case for regulatory exceptions that allowed innovative solutions

saving our clients over $18 million.

The

business case for strong writing is too compelling to be ignored,

although it commonly is in our profession. But you don't have to settle

for the status quo. By applying a few principles of what I call Power

Writing, you and your colleagues can get the results you've been missing

out on. What is Power Writing? It's writing that delivers the desired

result. To accomplish that, you need to attend to three basic

principles:

1. Purpose Driven: Define the Desired Result.

As Yogi Berra famously quipped, "If you don't know where you're going,

you'll end up somewhere else." Technical professionals often jump right

into writing without much planning, or a clear understanding of what it

is they're trying to accomplish. Everything you write has a purpose, but the chances are you don't really think about it.

You just start writing because you have something to say. Yet simply

communicating your message often falls short of getting the result you want.

Power Writing demands a plan,

what it is you want to achieve and how that will be facilitated through

your writing. At the most basic level, you are typically seeking to do

one of three things—inform, instruct, or influence. Each of these broad

objectives calls for a different approach to writing. When you're not

clear on your purpose, you're more likely to write a proposal that reads

like a technical report. Or a report that has no clear objective. Or a work

process description that seems to ignore the needs of the people

following it.

Once you have your purpose identified, the next step is to determine your Key Messages. These are the 3-5 things that you absolutely must communicate effectively to achieve your

purpose. For each Key Message, you then want to define the supporting

points that are needed to clarify and validate your point. This process

results in a detailed content outline that will guide your writing.

2. Reader Focused: Facilitate Message Reception. Achieving

your purpose is ultimately dependent upon your readers. It takes two to

have successful communication. I liken it to a forward pass in

football. The quarterback must deliver the ball on target, but the

receiver has to catch it. If you're like most, your focus as a writer is

on making the pass. But you need to give equal attention to making sure

it is received.

A

good example of this is email. If you send an email to a client or

colleague, you may feel you did your job. But if the recipient doesn't

read it or misunderstands it, don't you share some responsibility for

that outcome? Power Writing isn't just sending out the equivalent of

perfect spirals, but delivering it in a way that makes it more

catchable.

That happens in several ways. Foremost, you need to try to see the issue from your readers' perspective. Then they'll be more interested in what you have to say. A

common disconnect in our industry is approaching a project from a

purely technical perspective when the client is more concerned with the

business or stakeholder implications. You won't likely accomplish your

purpose in writing unless it aligns in some way with what your readers

want or value.

Many (if not most) technical professionals are ineffective writers. That fact is widely

acknowledged. The question is does anyone really care? I don't see A/E

firms investing much in helping their staff become more proficient

writers.

Perhaps

they haven't considered the costs of poor writing: Lost proposals, weak

marketing, unapproved solutions, project mistakes, client claims,

interoffice conflict, lost productivity—to name a few. I have seen all

of these over the years as a result of poorly written proposals,

reports, contracts, policies, correspondence, emails, or procedures.

On

the flip side, strong writing can yield substantial business benefits.

I'm hardly a distinguished writer, but I've compiled a 75% proposal win

rate over the last 20 years, producing more than $300 million in fees. I

helped my previous employer generate millions of dollars in new

business that started with prospective clients contacting us because of

something we'd written. I wrote letters to regulatory agencies making

the case for regulatory exceptions that allowed innovative solutions

saving our clients over $18 million.

The

business case for strong writing is too compelling to be ignored,

although it commonly is in our profession. But you don't have to settle

for the status quo. By applying a few principles of what I call Power

Writing, you and your colleagues can get the results you've been missing

out on. What is Power Writing? It's writing that delivers the desired

result. To accomplish that, you need to attend to three basic

principles:

1. Purpose Driven: Define the Desired Result.

As Yogi Berra famously quipped, "If you don't know where you're going,

you'll end up somewhere else." Technical professionals often jump right

into writing without much planning, or a clear understanding of what it

is they're trying to accomplish. Everything you write has a purpose, but the chances are you don't really think about it.

You just start writing because you have something to say. Yet simply

communicating your message often falls short of getting the result you want.

Power Writing demands a plan,

what it is you want to achieve and how that will be facilitated through

your writing. At the most basic level, you are typically seeking to do

one of three things—inform, instruct, or influence. Each of these broad

objectives calls for a different approach to writing. When you're not

clear on your purpose, you're more likely to write a proposal that reads

like a technical report. Or a report that has no clear objective. Or a work

process description that seems to ignore the needs of the people

following it.

Once you have your purpose identified, the next step is to determine your Key Messages. These are the 3-5 things that you absolutely must communicate effectively to achieve your

purpose. For each Key Message, you then want to define the supporting

points that are needed to clarify and validate your point. This process

results in a detailed content outline that will guide your writing.

2. Reader Focused: Facilitate Message Reception. Achieving

your purpose is ultimately dependent upon your readers. It takes two to

have successful communication. I liken it to a forward pass in

football. The quarterback must deliver the ball on target, but the

receiver has to catch it. If you're like most, your focus as a writer is

on making the pass. But you need to give equal attention to making sure

it is received.

A

good example of this is email. If you send an email to a client or

colleague, you may feel you did your job. But if the recipient doesn't

read it or misunderstands it, don't you share some responsibility for

that outcome? Power Writing isn't just sending out the equivalent of

perfect spirals, but delivering it in a way that makes it more

catchable.

That happens in several ways. Foremost, you need to try to see the issue from your readers' perspective. Then they'll be more interested in what you have to say. A

common disconnect in our industry is approaching a project from a

purely technical perspective when the client is more concerned with the

business or stakeholder implications. You won't likely accomplish your

purpose in writing unless it aligns in some way with what your readers

want or value.

Reader-focused writing also means making it user friendly. One of the best ways to do this is to convey your message as efficiently as possible.

Did you know it takes the average adult about one hour to read 35 pages

of text? You should write with the expectation that it won't be read

word for word (yes, even your emails). Make your main points skimmable.

Make effective use of graphics. Use words everyone understands. Write in a conversational tone that easily connects.

3. Engages the Heart: Move Your Readers to Act.

Of course, not everything you write is intended to spur your readers to

action. But the most important writing you do is when you want to

influence a particular response. It's unfortunate, then, that technical

professionals struggle so much with persuasive writing. A big part of

the problem is that they have been taught to write in a manner that is

fundamentally nonpersuasive.

Technical writing is by nature intellectual, objective, impersonal, and features-laden. This style of writing—which pervades our profession—avoids personal language, keeps opinions to ourselves, provides more detail than the audience needs, and buries the main selling points in information overload. It

may suffice when writing a study report, technical paper, or O&M

manual. But it is entirely the wrong approach when you want to persuade

clients, regulators, the public, or employees.

To

move your readers to act, you need to engage the heart. That's because

persuasion is driven by emotion and supported by logic—not the other way

around. It is the human spirit that influences and inspires, and there

is precious little of it evident in most of the writing we see in our

industry. If you want to be more persuasive, let me suggest you start by

dispatching the "technicalese" in favor of acknowledging in your

writing the humanity in both you and your audience.

I

think the power of writing has been grossly undervalued in the A/E

industry. So I want to devote the next few posts to explaining in more

detail how to become a Power Writer.

My 17-year-old daughter has decided to become an engineer, but she had no idea which

engineering discipline to choose. Since I have connections in the

profession, I began setting up appointments for her to meet with

different kinds of engineers to see which discipline appealed to her

most.

We

started with the two that I'm most familiar with—civil and

environmental. These engineers did a great job selling their specialty,

but none really connected with my daughter. Then one of my clients

arranged for her to tour the mechanical engineering department at

Virginia Tech. The light came on. She came back with an unexpected

amount of enthusiasm (after all, like many engineers, she had been

mainly drawn to the profession because she was good at math).

What

was it that caught her attention? Well, the robotics laboratory was

fascinating, of course. But the attraction went deeper. When she visited

the previous engineering offices, they inevitably pulled out plan sets

to show her their work. They designed things that others built. In the mechanical engineering lab, students designed, built, tested, and refined their work products. It was much more hands-on.

Now

I'm not going to suggest that one field of engineering is better than

another. That is a personal preference, and all engineering disciplines

do valuable work. But I'm convinced there is added benefit in being

closely connected with the desired end result. Ultimately, that's what

engineers are hired to deliver. Does that mean that engineers must build

what they design in order to be more valuable? No, but I do think many engineers could take a more active role in envisioning and shaping the final outcome.

I

have several engineer friends who work in manufacturing. In talking to

them about their work, the customer is typically a prominent part of the

conversation. This is particularly true among those who make products for other businesses. They have a keen understanding of how their products help their customers succeed.

Among

the engineers I work with in the AEC industry, not so much. Many of

them seem disconnected from the ultimate project outcomes. Why is the

client doing this? What is the business result that is needed? When I

pose these questions, I'm often disappointed how little many engineers

in our business understand the answers.

This

problem isn't limited to the engineers, by the way. Architects can also

be prone to overlooking the client's desired end results. A common

client complaint is that many architects seem to favor form over

function, emphasizing aesthetic design values over practical priorities

(such as staying within the client's budget!). One of my favorite

architects once told me that his first responsibility was to create

spaces that maximize functionality. Aesthetics take precedent, he said,

only when the client has designated that as a critical function of the

building.

So

how can we do a better job connecting our work with the outcomes that

ultimately drive our projects? If you follow this blog, you no doubt

recognize that I've touched on this general theme before. I keep

revisiting it because I keep seeing evidence that it is needed. So here

are a few recommendations on how to make your work more results oriented:

Uncover the strategic drivers behind your projects. A/E projects typically help clients achieve strategic business or mission goals.

Do you know what those are? Can you describe specifically how your

design or solution will enable the client to fulfill those goals?

Don't overlook the human dimension of your solutions. People

are always the primary benefactors of your projects. Yet many technical

professionals tend to be more focused on the technical aspects of the

work than how people are affected. When working on a technical problem, be sure to consider the human consequences. Your solution should explicitly address both the problem and how it impacts people.

Learn to describe your work in terms of its ultimate outcomes. I often point to our project descriptions

as evidence that improvement is needed in this area. What do they

describe? Typically the tasks performed. Sometimes the technical

problem. Rarely do I read, in specific terms, of how the project helped

the client be successful. The same is often true in our conversations

with existing or prospective clients.

Promote greater cross-disciplinary collaboration. One of the most common project delivery problems I encounter is inadequate coordination between disciplines. This is a primary cause of design-related construction claims. But true collaboration

across disciplines goes deeper than merely avoiding mistakes. It

leverages the different perspectives and strengths of each discipline to

deliver a more encompassing, higher value solution—one that looks

beyond the details of project execution to achieving the project's

ultimate goals.

Follow the project all the way through. Sometimes A/E firms are contracted through construction and even start-up. That enables you to have a more direct role in ensuring the project's ultimate success. But what if the contract ends with the completed design? I urge that you keep in contact with the client, offering advice and answering questions, helping the finished project achieve its stated goals. It's not all that uncommon that design-related problems occur during construction or operation that the design firm is not made aware of. It's best to monitor project progress to the end to be in a position to help and perhaps learn from your mistakes.

The

most valuable thing we do in our industry is not engineering and

architecture, but helping clients realize their dreams and ambitions. We

solve problems that hamper their business performance and create

facilities that enable their success. When we get closer to the desired

end results, the perceived value of our work increases. Agree or

disagree? Do you have other suggestions for how our profession can be

more directly involved in delivering business results?

My 17-year-old daughter has decided to become an engineer, but she had no idea which

engineering discipline to choose. Since I have connections in the

profession, I began setting up appointments for her to meet with

different kinds of engineers to see which discipline appealed to her

most.

We

started with the two that I'm most familiar with—civil and

environmental. These engineers did a great job selling their specialty,

but none really connected with my daughter. Then one of my clients

arranged for her to tour the mechanical engineering department at

Virginia Tech. The light came on. She came back with an unexpected

amount of enthusiasm (after all, like many engineers, she had been

mainly drawn to the profession because she was good at math).

What

was it that caught her attention? Well, the robotics laboratory was

fascinating, of course. But the attraction went deeper. When she visited

the previous engineering offices, they inevitably pulled out plan sets

to show her their work. They designed things that others built. In the mechanical engineering lab, students designed, built, tested, and refined their work products. It was much more hands-on.

Now

I'm not going to suggest that one field of engineering is better than

another. That is a personal preference, and all engineering disciplines

do valuable work. But I'm convinced there is added benefit in being

closely connected with the desired end result. Ultimately, that's what

engineers are hired to deliver. Does that mean that engineers must build

what they design in order to be more valuable? No, but I do think many engineers could take a more active role in envisioning and shaping the final outcome.

I

have several engineer friends who work in manufacturing. In talking to

them about their work, the customer is typically a prominent part of the

conversation. This is particularly true among those who make products for other businesses. They have a keen understanding of how their products help their customers succeed.

Among

the engineers I work with in the AEC industry, not so much. Many of

them seem disconnected from the ultimate project outcomes. Why is the

client doing this? What is the business result that is needed? When I

pose these questions, I'm often disappointed how little many engineers

in our business understand the answers.

This

problem isn't limited to the engineers, by the way. Architects can also

be prone to overlooking the client's desired end results. A common

client complaint is that many architects seem to favor form over

function, emphasizing aesthetic design values over practical priorities

(such as staying within the client's budget!). One of my favorite

architects once told me that his first responsibility was to create

spaces that maximize functionality. Aesthetics take precedent, he said,

only when the client has designated that as a critical function of the

building.

So

how can we do a better job connecting our work with the outcomes that

ultimately drive our projects? If you follow this blog, you no doubt

recognize that I've touched on this general theme before. I keep

revisiting it because I keep seeing evidence that it is needed. So here

are a few recommendations on how to make your work more results oriented:

Uncover the strategic drivers behind your projects. A/E projects typically help clients achieve strategic business or mission goals.

Do you know what those are? Can you describe specifically how your

design or solution will enable the client to fulfill those goals?

Don't overlook the human dimension of your solutions. People

are always the primary benefactors of your projects. Yet many technical

professionals tend to be more focused on the technical aspects of the

work than how people are affected. When working on a technical problem, be sure to consider the human consequences. Your solution should explicitly address both the problem and how it impacts people.

Learn to describe your work in terms of its ultimate outcomes. I often point to our project descriptions

as evidence that improvement is needed in this area. What do they

describe? Typically the tasks performed. Sometimes the technical

problem. Rarely do I read, in specific terms, of how the project helped

the client be successful. The same is often true in our conversations

with existing or prospective clients.

Promote greater cross-disciplinary collaboration. One of the most common project delivery problems I encounter is inadequate coordination between disciplines. This is a primary cause of design-related construction claims. But true collaboration

across disciplines goes deeper than merely avoiding mistakes. It

leverages the different perspectives and strengths of each discipline to

deliver a more encompassing, higher value solution—one that looks

beyond the details of project execution to achieving the project's

ultimate goals.

Follow the project all the way through. Sometimes A/E firms are contracted through construction and even start-up. That enables you to have a more direct role in ensuring the project's ultimate success. But what if the contract ends with the completed design? I urge that you keep in contact with the client, offering advice and answering questions, helping the finished project achieve its stated goals. It's not all that uncommon that design-related problems occur during construction or operation that the design firm is not made aware of. It's best to monitor project progress to the end to be in a position to help and perhaps learn from your mistakes.

The

most valuable thing we do in our industry is not engineering and

architecture, but helping clients realize their dreams and ambitions. We

solve problems that hamper their business performance and create

facilities that enable their success. When we get closer to the desired

end results, the perceived value of our work increases. Agree or

disagree? Do you have other suggestions for how our profession can be

more directly involved in delivering business results?

What's necessary to build

sustainable business success? Lasting client relationships. Imagine if

you never had any repeat business. Could you survive? Highly unlikely.

So keeping existing clients deserves every bit the focus that finding new ones does.

It's

interesting, then, that most firms pay substantially more attention to

winning new clients than taking care of their current ones. If you doubt that conclusion, consider these questions:

How much of your strategic plan is devoted to improving business

development compared to improving client care? Do you have a sales

process, but not a relationship building process? Which receives more of

your training budget? Or more discussion in staff meetings?

Obviously, there's

nothing wrong with giving emphasis to business development. In fact,

most firms could stand to give it more. But let's not overlook the fact

that the best way to grow your business is usually through existing

client relationships. Are you taking steps to make those relationships

stronger? Here are five suggestions to do just that:

1. Create a client relationship building process.

You probably have a few individuals in your firm who are skilled at

nurturing strong client relationships. And some who aren't. Therein lies

the problem—a crucial function that's left to individual competency and

initiative. You don't manage projects that way; there are standard

procedures to ensure some measure of consistency. In fact there are many

less critical activities in your firm that have been defined as a

repeatable process.

So

why not an approach for building client relationships? Of course, there

are interpersonal dynamics in relationships that are not easily

programed. But if marriages can be strengthened by applying generic tips

from a book or conference, such improvements can certainly be realized

with clients. The key is to define certain elements of relationship

building that lend themselves to being replicated across the

organization. Here's how to get started:

What's necessary to build

sustainable business success? Lasting client relationships. Imagine if

you never had any repeat business. Could you survive? Highly unlikely.

So keeping existing clients deserves every bit the focus that finding new ones does.

It's

interesting, then, that most firms pay substantially more attention to

winning new clients than taking care of their current ones. If you doubt that conclusion, consider these questions:

How much of your strategic plan is devoted to improving business

development compared to improving client care? Do you have a sales

process, but not a relationship building process? Which receives more of

your training budget? Or more discussion in staff meetings?

Obviously, there's

nothing wrong with giving emphasis to business development. In fact,

most firms could stand to give it more. But let's not overlook the fact

that the best way to grow your business is usually through existing

client relationships. Are you taking steps to make those relationships

stronger? Here are five suggestions to do just that:

1. Create a client relationship building process.

You probably have a few individuals in your firm who are skilled at

nurturing strong client relationships. And some who aren't. Therein lies

the problem—a crucial function that's left to individual competency and

initiative. You don't manage projects that way; there are standard

procedures to ensure some measure of consistency. In fact there are many

less critical activities in your firm that have been defined as a

repeatable process.

So

why not an approach for building client relationships? Of course, there

are interpersonal dynamics in relationships that are not easily

programed. But if marriages can be strengthened by applying generic tips

from a book or conference, such improvements can certainly be realized

with clients. The key is to define certain elements of relationship

building that lend themselves to being replicated across the

organization. Here's how to get started:

- Identify common traits among your best client relationships

- Determine the steps that were taken to build those relationships

- Develop a relationship building process based on your assessment

- Pilot this process with a few clients with growth potential

2. Clarify mutual expectations.

For every project, you develop a scope of work, schedule, and budget

that the client reviews and approves. But many aspects of the working

relationship—such as communication, decision making, client involvement,

managing changes, and monitoring satisfaction—are not discussed and

explicitly agreed upon with the client. In my experience, most service breakdowns are

caused by unknown or misunderstood expectations.

To

delight clients and win their loyalty, you need to know how they like

to be served. Over time this becomes clearer, but you may not make it

that far. How much better to simply ask what the client's expectations

are up front, as well as to share what you'd like from the client in return to make the relationship stronger? This is a practice I call "service benchmarking," and you may find my Client Service Planner helpful in this regard.

3. Increase client touches. These are simply the direct and indirect interactions you have with clients. Too often these touches are limited to times of necessity. This is the project manager who only calls when there's a problem. Or the principal who is out of sight until the next RFP approaches. Clients notice. Perhaps the biggest complaint I've heard in the many client interviews I've conducted is the failure of A/E firms to communicate proactively.

What are some ways to increase client touches? Consider the following:

- Invite the client to your project kickoff meeting

- Send monthly project status reports

- Share internal project meeting minutes and action items

- Call to discuss issues before they become problems

- Send articles, papers, reports,and tools of interest to the client

4. Periodically seek performance feedback. Having clarified expectations in advance, it's important to check in on occasion

to ask how well you're doing. The frequency and timing of these

discussions is hopefully one of the expectations you established during

the benchmarking step. This is another valuable way to increase client

touches.

About 1 in 4 firms in this business formally solicit client feedback, and reportedly only about 5

percent do it regularly. So there's a tremendous opportunity for you to

distinguish your firm with your clients. Here are some tips for getting

effective feedback:

- Have someone not directly involved in the project do this

- Mix both discussions and a standard questionnaire

- Talk to multiple parties in the client organization if possible

- Be sure to follow up promptly to any concerns identified

5. Don't disappear between projects.

This relates back to my advice about client touches; don't limit them

only to when it's in your self interest. Keep in touch with the client

after the project is completed—for the client's sake. For one thing, the

real value of your work isn't realized until the facility you designed

is put into operation or the recommendations in your report are acted

upon. You want to be talking with the client when these moments of

truth happen, whether it's part of your contract or not.

Offer

whatever support you can to further ensure the project's success. But

you also want to demonstrate your interest in the client's success

outside the project. Provide helpful information and advice, in person,

over the phone, and digitally (as part of your content marketing effort).

The time between projects (assuming you've won the client's trust to do

another project together) can be a productive relationship building

time, because it's often unexpected. Having met the client's

expectations during the project, this is another chance to exceed them.

In my last post

I argued that all project managers should be contributing to their

firm's sales efforts. Only half do, according to the Zweig Group. A

prominent reason for the low participation is that most PMs don't feel

competent or comfortable in this role (and this is also true of many who

are involved in sales!). As I wrote previously, I'm confident

that capable PMs can successfully transfer their project management

skills to selling—it's much the same skill set. Here are some

suggestions for helping them make that transition:

Train them in a service-centered approach to selling. The problem most PMs have with selling is that they have an overwhelmingly negative impression

of salespeople. They have their own experiences as a buyer, and that

taints their view of selling. But rather than avoid selling, they should

be striving to change the experience for those who buy the firm's

services. Serve prospective clients rather than sell to them.

"High-end selling and consulting are not different and separate skills,"

observes sales researcher Neil Rackham, "When we are watching the very

best [seller-doers] in their interactions with clients, we cannot tell

whether they are consulting, selling, or delivering." For the A/E

professional, this means uncovering needs, offering advice, recommending

solutions—giving a meaningful sample of what it will be like working

together under contract. This kind of approach takes the sting out of

selling for both the PM and the client.

In my last post

I argued that all project managers should be contributing to their

firm's sales efforts. Only half do, according to the Zweig Group. A

prominent reason for the low participation is that most PMs don't feel

competent or comfortable in this role (and this is also true of many who

are involved in sales!). As I wrote previously, I'm confident

that capable PMs can successfully transfer their project management

skills to selling—it's much the same skill set. Here are some

suggestions for helping them make that transition:

Train them in a service-centered approach to selling. The problem most PMs have with selling is that they have an overwhelmingly negative impression

of salespeople. They have their own experiences as a buyer, and that

taints their view of selling. But rather than avoid selling, they should

be striving to change the experience for those who buy the firm's

services. Serve prospective clients rather than sell to them.

"High-end selling and consulting are not different and separate skills,"

observes sales researcher Neil Rackham, "When we are watching the very

best [seller-doers] in their interactions with clients, we cannot tell

whether they are consulting, selling, or delivering." For the A/E

professional, this means uncovering needs, offering advice, recommending

solutions—giving a meaningful sample of what it will be like working

together under contract. This kind of approach takes the sting out of

selling for both the PM and the client.

Budget time specifically for sales. The other big excuse for why PMs don't sell is that there isn't enough time. Or more specifically, that spending time developing new business subtracts from time on billable project work.

Given the obsession with utilization that exists in many firms, it's

hardly surprising that this perception is so prevalent. But the claim is

seldom supported by the facts.

Nearly all PMs

work a substantial number of nonbillable hours, a portion of which could

be devoted to sales activities. The problem is that these hours are

rarely budgeted or managed, so that in effect selling is done with

leftover time. And who has surplus time left over? You can minimize the

concern that selling displaces billable hours by managing your business

development efforts like project work, including budgeting a portion

existing nonbillable hours for this purpose.

Fit sales responsibilities to PMs' individual strengths. Selling is not as monolithic an activity as many presume, nor does it favor a specific personality type. There is a potential sales role for virtually anyone

in your firm, including your PMs. Some are comfortable at networking

functions, others better at one-on-one conversations. Some are

big-picture strategists, others more analytical problem solvers. Some

are competent writers, others better in communicating verbally. Some may

be capable in making sales calls, others are better assigned to doing

research, writing proposals, or developing solutions. The key is fitting the right people to the right roles.

PMs often claim that they don't have the personality to sell. But the research finds no real correlation

between personality type and sales success. Fit, again, is the critical

strategy. Help PMs shape their sales responsibilities around both their

capabilities and their personality.

Bolster your marketing efforts.

Technical professionals typically struggle more in starting the sales process than in closing the sale. They often dislike prospecting for new

leads, especially making cold calls, attending networking events, and initiating client relationships.

Effective marketing can shorten the sales cycle by bringing interested

prospects to your door. Most PMs are much more comfortable picking up

the sales effort at this point.

Where

to start? Consider the marketing tactics that have proven most effective for professional service firms. These activities typically

require significant support from the firm's content experts, which

likely will include at least some of your PMs. They don't want to make cold

calls or work the room? How about giving a presentation, helping write

an article, or contributing to a seminar? Involvement in marketing not only

builds the firm's brand, but the personal brands of your PMs—making it

easier for them to sell.

Increase collaboration. Selling

is often a lonely activity, which further magnifies the discomfort most

PMs have with it. That's why I favor building your sales team, where those involved in sales regularly meet together, share information,

encourage one another, plan sales pursuits, and hold each other

accountable. Have members of the team work together on sales calls when

that makes sense. The investment you make in promoting collaboration, in

my experience, will more than pay off in increased sales productivity.

Provide ongoing coaching. Sales coaching can dramatically improve results

for your PMs engaged in selling. If you do training, as suggested

above, you'll need to reinforce it to make it successful—meaning

real-time feedback and instruction. Organizing your sales team can

provide opportunities for peer-to-peer coaching. Pairing up PMs with

your best sellers is another option. Or you may decide to seek outside

support from a consultant. A good coach helps build both the PM's

capabilities and motivation in the most effective manner—on the job.

Being a project manager is a

tough job. I get that. PMs are charged with keeping the client happy,

delivering a technically sound solution, meeting the budget and

schedule, coordinating the project team, interacting with multiple

project stakeholders, ensuring the quality of deliverables, and often a

myriad of other management, supervisory, and administrative duties

outside of their project work.

Did

I mention business development? Is it fair to add that responsibility

to an already long to-do list? According to a Zweig Group survey, only

4% of PMs claimed no involvement in BD activities. Over 80% indicated

they contribute to proposals, 60% make presentations, and 55%

participate in sales activities. That last number surprises me. I think

it should be closer to 100%.

I

can hear the howls of disapproval. Numerous PMs have told me they don't

have the time or the personality or the desire to get involved in

selling. Many firms seem to concur, putting little if any pressure on

PMs to actively support sales activities. But there are several reasons

why I believe PMs are needed to have a truly successful sales process:

Being a project manager is a

tough job. I get that. PMs are charged with keeping the client happy,

delivering a technically sound solution, meeting the budget and

schedule, coordinating the project team, interacting with multiple

project stakeholders, ensuring the quality of deliverables, and often a

myriad of other management, supervisory, and administrative duties

outside of their project work.

Did

I mention business development? Is it fair to add that responsibility

to an already long to-do list? According to a Zweig Group survey, only

4% of PMs claimed no involvement in BD activities. Over 80% indicated

they contribute to proposals, 60% make presentations, and 55%

participate in sales activities. That last number surprises me. I think

it should be closer to 100%.

I

can hear the howls of disapproval. Numerous PMs have told me they don't

have the time or the personality or the desire to get involved in

selling. Many firms seem to concur, putting little if any pressure on

PMs to actively support sales activities. But there are several reasons

why I believe PMs are needed to have a truly successful sales process:

PMs are the primary contacts with clients.

Or at least they should be. PMs are typically the ones who work closest

with clients on projects. I've seen situations where principals or

department heads assumed this role, but it's less than ideal. In

interviewing hundreds of clients over the years, it's clear that the

overwhelming majority favor strong PMs who take charge of ensuring

project success and serve as the primary liaison with the client and

other stakeholders. This role alone makes PMs the logical choice to

support the firm's sales efforts.

PMs are one of the critical assets you are selling. You

can try to sell the firm's qualifications, but most clients want to

know about the individuals who specifically will be working on their

project. Chief among these project team members is the PM. Who can best

sell the PM's strengths to the client? The PM, ideally. Not by telling,

but by demonstrating. The nature of professional services is that we

sell the people who perform the services. And the person who most needs

to gain the client's confidence, in most cases, is the PM.

Selling should be about serving.

I've encountered many PMs who were reluctant to sell to existing

clients because they feared it might taint the project relationship. I

understand their concern, if you look at it through the lens of

traditional selling. But the most effective way to develop new business

with clients in the A/E business is not by pushing your services. It's

about serving—about meeting needs, providing advice, identifying

solutions. If PMs really care about their relationship with clients,

they should be looking for other ways to help.

PMs have the right skill set for selling. If

you accept my previous point that serving clients is the best way to

"sell," then it follows that PMs (good ones, at least) are particularly

suited for this task. Who better to help clients? Strong PMs generally

are more effective at bringing a broader, multidisciplinary perspective

to the project than the technical practitioners who will make up the

rest of the project team. PMs should have client skills that readily

transfer to a service-centered approach to sales.

Despite claims to the

contrary, the skill set for project management is much the same as for

selling in this manner: Interpersonal skills, communication, problem

solving, planning, collaboration, follow-through, etc. Any PM who cannot

sell is probably not very good at project management either. And the

claim that they don't have the personality? Research shows no

correlation between personality and sales success.

Participation in sales increases a sense of ownership.

There's something about building a relationship from scratch with a

client that engenders a deeper sense of ownership of that relationship.

My observation is that PMs who are actively involved in selling are

generally more committed to keeping clients happy. Perhaps that's

because they engaged the client before the relationship could be

mistaken as simply completing a scope of work.

At a minimum, I think it's

critically important to involve the PM in defining the proposal

strategy, winning the shortlist interview, and negotiating the contract.

PMs should always be involved in determining the scope, schedule, and

budget of the project—they shouldn't be asked to deliver something they

had no part in defining.

Agree or disagree? I'd love to

hear what you think about the PM's role in sales. Next post I'll offer

some suggestions for helping PMs succeed in selling.

So when was the

last time your firm rebranded itself? Most of my clients have at least

tweaked their brand in the last decade—or so they thought. More

accurately, they redesigned their logo, modified their color scheme,

rewrote their positioning statement, overhauled their website, etc. In

other words, they changed how they marketed themselves.

But that's not

branding. Not really. It's disappointing that most marketers don't

understand this, but who can blame them? There's a lot of confusion

about this subject in the literature. Marketing people naturally view

branding as something within their domain. But the consensus of brand

experts points to something much more complex than a marketing function.

So when was the

last time your firm rebranded itself? Most of my clients have at least

tweaked their brand in the last decade—or so they thought. More

accurately, they redesigned their logo, modified their color scheme,

rewrote their positioning statement, overhauled their website, etc. In

other words, they changed how they marketed themselves.

But that's not

branding. Not really. It's disappointing that most marketers don't

understand this, but who can blame them? There's a lot of confusion

about this subject in the literature. Marketing people naturally view

branding as something within their domain. But the consensus of brand

experts points to something much more complex than a marketing function.

In simple

terms, brand is how your firm is perceived in the marketplace. It is

primarily shaped through the direct and indirect interactions customers

and others have with your firm. Marketing can influence those

perceptions (through its indirect interactions), but eventually direct

interactions form the bedrock of your brand. Your real brand is

substance, not image.

So what does

this mean? True rebranding is about changing the substance of the

interactions you have with clients and others. It's about creating

better experiences, which lead to positive expectations about future

experiences with your firm. (I like Sean Adam's definition of brand:

"It's a promise of an experience.")

It's about

backing up your marketing claims through action. Focused on clients?

Show it! Design excellence? Let's see what you got! Superior quality?

Prove it! Great at collaboration and team building? Demonstrate the

benefits! This is why marketing can't create your brand, because

ultimately you have to deliver it. Clients have to experience it.

This is not to

diminish the contributions of marketing. On the contrary, I'm a strong

advocate for effective marketing. I think as an industry that we

generally underappreciate the value of marketing. Marketers are too often marginalized

as tactical specialists rather than strategic partners. The best

marketing comes when there's real substance to sell. Invite marketers

into the discussion about how to create a genuine, deliverable brand.

For a step-by-step approach to building your brand, check out this previous post.

A few years ago

I was helping an engineering firm prepare a proposal to what would have

been a new client. A coastal city wanted to combine two smaller

wastewater treatment plants into one new or expanded one. I was working

with two seasoned engineers, both with over 35 years of experience. They

were abundantly qualified to do the work.

Early in our

discussions, I asked the question I typically ask when planning a

proposal, "Why is the client doing this project now?" Despite having had

a couple conversations with the client, neither of my collaborators

could confidently answer the question. "Well, let's make sure we clarify

what's driving this project next time you talk to them," I urged.

Another meeting

with the client followed. We had prepared a list of questions we wanted

answered, but somehow my question was never posed. When I later pressed

the point that it was important to know the answer, one of the

engineers responded in frustration, "What difference does it make? We

can do the work!"

Unfortunately,

his response is hardly unique. I've asked some variation of that

question hundreds of times over the years without getting a satisfactory

answer from the proposal team. It's symptomatic of a larger problem:

The failure of many in the A/E industry to see the value of connecting

their work to the client's higher-value strategic needs or business

goals.

Need further evidence?

Read your firm's project descriptions. Most I've seen do a poor job

describing why the project was necessary or important. Instead they

focus on the scope of work performed. How do you think the client would

describe their project? Much differently, don't you think?

I once was

responsible for marketing for a new national environmental company

formed through the merger of six firms. I wanted to produce more

meaningful project descriptions, so I divided the template for

collecting project information into three parts: (1) What was the

problem we solved? (2) What did we do? (3) How did we add value?

The company had

some great projects on its resume—pioneering industry milestones,

technology innovations, millions of dollars in savings for our Fortune

100 clients. Yet I was shocked to see how much my colleagues struggled

to supply the project information I had requested. No problem with the

scope of work, of course. But they found it difficult to associate the

problems solved with our clients' business objectives. And many

completely whiffed on the question about added value.

So, we're

supposed to make the case that we're the best firm for the job, but we

can't describe why our past clients benefited from hiring us versus any

other environmental firm? That, my friends, is the fundamental

definition of a commodity:

A few years ago

I was helping an engineering firm prepare a proposal to what would have

been a new client. A coastal city wanted to combine two smaller

wastewater treatment plants into one new or expanded one. I was working

with two seasoned engineers, both with over 35 years of experience. They

were abundantly qualified to do the work.

Early in our

discussions, I asked the question I typically ask when planning a

proposal, "Why is the client doing this project now?" Despite having had

a couple conversations with the client, neither of my collaborators

could confidently answer the question. "Well, let's make sure we clarify

what's driving this project next time you talk to them," I urged.

Another meeting

with the client followed. We had prepared a list of questions we wanted

answered, but somehow my question was never posed. When I later pressed

the point that it was important to know the answer, one of the

engineers responded in frustration, "What difference does it make? We

can do the work!"

Unfortunately,

his response is hardly unique. I've asked some variation of that

question hundreds of times over the years without getting a satisfactory

answer from the proposal team. It's symptomatic of a larger problem:

The failure of many in the A/E industry to see the value of connecting

their work to the client's higher-value strategic needs or business

goals.

Need further evidence?

Read your firm's project descriptions. Most I've seen do a poor job

describing why the project was necessary or important. Instead they

focus on the scope of work performed. How do you think the client would

describe their project? Much differently, don't you think?

I once was

responsible for marketing for a new national environmental company

formed through the merger of six firms. I wanted to produce more

meaningful project descriptions, so I divided the template for

collecting project information into three parts: (1) What was the

problem we solved? (2) What did we do? (3) How did we add value?

The company had

some great projects on its resume—pioneering industry milestones,

technology innovations, millions of dollars in savings for our Fortune

100 clients. Yet I was shocked to see how much my colleagues struggled

to supply the project information I had requested. No problem with the

scope of work, of course. But they found it difficult to associate the

problems solved with our clients' business objectives. And many

completely whiffed on the question about added value.

So, we're

supposed to make the case that we're the best firm for the job, but we

can't describe why our past clients benefited from hiring us versus any

other environmental firm? That, my friends, is the fundamental

definition of a commodity:

- A commodity is a product or service that is widely available and interchangeable with what competitors offer.

The fast track to commoditization is to be just another competent service provider.

If you can't describe how you meet strategic needs, help solve business

problems, or deliver added value—well, you're in good company. That's

where most A/E firms reside. But, of course, the goal is to stand out in

the crowd, not fit in.

That

distinction could start by simply knowing the answer to the why question

above. In other words: "How do we help our clients be successful?" No,

really. Not the marketing slogan kind of commitment to enabling success.

But real business solutions delivered through your technical expertise.

If you're not routinely making that connection now, let me urge you to

make it a priority. Want to brainstorm some ideas, no obligation? Give

me a holler.

The verdict is in: Writing fewer proposals typically increases both your win rate

and your sales. That, at least, is the consensus of the many sales and

proposal experts I "surveyed" via a Google search. That has also been my

experience over the last 25 years working with a variety of

engineering, environmental, and architectural firms.

But many firm

principals aren't buying it. Not in practice, at least. They find it

hard to "miss opportunities" by being more selective in the proposals

they submit. Several have explained to me that while that maxim may work

for most, it doesn't apply to their firm, office, or market sector.

They fear dire consequences if they reduced the number of proposals.

Inevitably, these "volume sellers" have a low win rate. Their business development costs

are often inordinately high, and their profits are usually lower. It's

not uncommon for volume sellers to pursue a higher percentage of

price-driven selections, which would seem to substantiate their

conviction that more proposals equals more sales.

They may be

right, but I doubt it. For one thing, that approach to developing new

business inherently erodes the perceived value of their services. My

take after watching business development trends for decades is that

indiscriminate selling reinforces indiscriminate buying (e.g., selecting

on the basis of low price). When you shortchange the sales process by

simply responding to RFPs, you shortchange the opportunity to establish

your value proposition.

Still not convinced? I offer the following additional reasons why you should be writing fewer proposals:

Proposals are costly, but the greatest cost is opportunity cost. Proposals

constitute roughly half of the typical A/E firm's BD budget. But for

many firms, the budget share is still higher. And as proposal costs

increase, there is usually a corresponding drop in ROI (i.e., win rate).

That's because the larger expenditure is rarely an investment in better

proposals, but in more proposals.

It's fairly

typical for volume sellers to spend about 70% of their proposal budget

on writing losing proposals. But that's not the worst of it. The greater

cost is that those hours could have been diverted to higher-value BD

activities, such as positioning their firm for success in advance of the

RFP. I remain convinced that the vast majority of awards go to the

firms that invest substantially in the pre-RFP sales process.

You need to invest more in your best proposal opportunities. What

about the argument that

most of the cost is borne by overhead staff who you have to pay for

anyway? You still suffer opportunity costs because they could have spent

more time on more promising proposal efforts (not to mention marketing,

which is frequently neglected in A/E firms). Plus, if most of your

proposal labor cost comes from marketing staff, I would question your

commitment to producing winning proposals.

The verdict is in: Writing fewer proposals typically increases both your win rate

and your sales. That, at least, is the consensus of the many sales and

proposal experts I "surveyed" via a Google search. That has also been my

experience over the last 25 years working with a variety of

engineering, environmental, and architectural firms.

But many firm

principals aren't buying it. Not in practice, at least. They find it

hard to "miss opportunities" by being more selective in the proposals

they submit. Several have explained to me that while that maxim may work

for most, it doesn't apply to their firm, office, or market sector.

They fear dire consequences if they reduced the number of proposals.

Inevitably, these "volume sellers" have a low win rate. Their business development costs

are often inordinately high, and their profits are usually lower. It's

not uncommon for volume sellers to pursue a higher percentage of

price-driven selections, which would seem to substantiate their

conviction that more proposals equals more sales.

They may be

right, but I doubt it. For one thing, that approach to developing new

business inherently erodes the perceived value of their services. My

take after watching business development trends for decades is that

indiscriminate selling reinforces indiscriminate buying (e.g., selecting

on the basis of low price). When you shortchange the sales process by

simply responding to RFPs, you shortchange the opportunity to establish

your value proposition.

Still not convinced? I offer the following additional reasons why you should be writing fewer proposals:

Proposals are costly, but the greatest cost is opportunity cost. Proposals

constitute roughly half of the typical A/E firm's BD budget. But for

many firms, the budget share is still higher. And as proposal costs

increase, there is usually a corresponding drop in ROI (i.e., win rate).

That's because the larger expenditure is rarely an investment in better